‘Thou shalt not kill’ (Exodus 20)

‘But I say to you, Do not resist an evildoer.’ (Matthew 7)

In this blog I shall look at these two verses, then address church history before offering my own justification for rejecting pacifism.

The Scriptures

The translation of one of the ten commandments as a condemnation of ‘killing’ as opposed to ‘murder’ dates from Wycliffe’s translation, and is also found in the Geneva bible as well as the King James. However in context it makes no sense; in the following chapter, capital punishment is commanded for a number of crimes including murder and kidnapping. It is clear therefore that the translation offered by many, more modern translations of ‘you shall not murder’ is more accurate.

The Matthew 7 passage has often been taken to demand a more radical attitude of Christians. There are two specific elements to keep in mind; the first is the argument that many of Jesus’ teachings are not intended to be taken literally, seeking to make His point by hyperbole. This reflects the style of teaching of the rabbis of the time, and is what we in fact do with many others of His teachings.

‘They are God’s servants, agents of wrath to bring punishment on the wrongdoer.’ (Romans 13) This is clear teaching that we are to be protected from evil by the state; we need to bear in mind that Paul was writing this at a time when the Roman state was an aggressive, imperialistic occupier of Judaea. Given this context, the pacifist Christian needs to assert that they can never accept a role in the state – but see below.

A final consideration is that Paul chose the equipment of a soldier as the basis for his teaching about the armour of God (Ephesians 6). If such individuals were by definition evil as a result of their profession, then it is odd that Paul chose the image; indeed I remember a liberal Rector once objecting to the imagery on that basis!

Two challenging Old Testament passages

These are fascinating. Firstly:

‘These are the nations the Lord left to test all those Israelites who had not experienced any of the wars in Canaan (he did this only to teach warfare to the descendants of the Israelites who had not had previous battle experience): the five rulers of the Philistines, all the Canaanites, the Sidonians, and the Hivites living in the Lebanon mountains from Mount Baal Hermon to Lebo Hamath. They were left to test the Israelites to see whether they would obey the Lord’s commands, which he had given their ancestors through Moses.’ (Judges 3)

Let’s read that again:

‘[God] did this only to teach warfare to the descendants of the Israelites who had not had previous battle experience’

Wow! A reminder that God’s agenda is not necessarily what we are comfortable with.

Secondly:

‘King David rose to his feet and said: “Listen to me, my fellow Israelites, my people. I had it in my heart to build a house as a place of rest for the ark of the covenant of the Lord, for the footstool of our God, and I made plans to build it. But God said to me, ‘You are not to build a house for my Name, because you are a warrior and have shed blood.’ (1 Chronicles 28)

Note that God does endorse Solomon to build the temple despite the fact that he was also involved in warfare. Perhaps God is hinting at David’s murder of Uriah, or perhaps it reflects the fact that he did kill people himself, starting from Goliath. Certainly overall the Old Testament gives no excuse to argue for an absolute ban on involvement in warfare.

Church history

It is widely asserted that the early church opposed military service. Much is said on the topic, and the view of the early church seems to be very mixed, with strong defences of pacifism from both Origen and Tertullian, yet there is clear evidence of Christians being present at all levels in the Roman army and government before Constantine. Ronald Sider, who is from a church that holds a pacifist position, has produced a book based on his PhD that offers the primary sources on the topic. The conclusion that seems to emerge is that there wasn’t a clear consensus on the matter, and it is important to recognise that the religious component of army service muddies the waters.

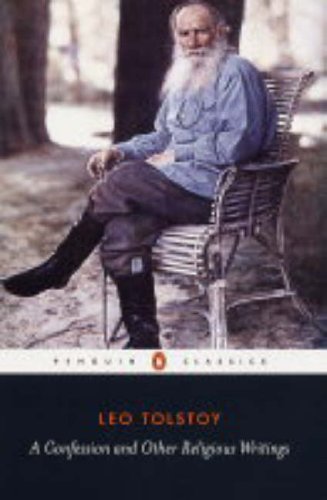

With the Roman Empire becoming Christian, the issue almost entirely disappears, though a few marginal groups seem to endorse it. However at the time of the Reformation, two significant groups adopt a pacifist stand: the Anabaptists – who develop into the Mennonites and Amish – as well as the Quakers. Tolstoy also adopts it as part of his theology in the late 19th century. The problem of the approach was demonstrated when the pre-revolutionary Quaker dominated government of Pennsylvania collapsed in the face of the Indian war, for which the state, lacking a militia, was ill prepared. Twentieth century conscription led to a number of responses, ranging from active battlefield involvement in non-combat roles (thus the Quaker Ambulance Service) via other forms of service – such as farm work – through to total resistance to any involvement.

Tolstoy adopted pacifism as part of his theology in the late 19th century, and this influenced Gandhi’s non-violence ideology, with whom Tolstoy was in correspondence. The idealism of the 60s reinvigorated the idea, with the Beatles’ song ‘All You Need is Love’ being the proselytising anthem of the movement, though for many the chaos ensuing from the sixties led to disenchantment. This simplistic idealism leaked into parts of the church after the 60s, perhaps encouraging naïve attitudes to the Soviet and other dictatorships in 70s, as well as strengthening opposition to nuclear weapons, though a significant element in the church adopted a belief in nuclear pacifism, arguing that ‘a war involving nuclear weapons is not a winnable or “just” war, and is unjustifiable because of its uniquely devastating consequences’.

Theological considerations

The traditional ‘move’ in the ethical debate is to separate the role of the Christian as an individual from what they do as a officer of state. This is criticised by the pacifist tradition in favour of arguing that it is God’s command not to resist evil / take revenge etc., and this is not challenged by the change of hats. It is my contention that this fails to note the role of parents in using force and ensuring justice for their children; if Molly is beating up her little brother Timothy, it is clearly the duty of the parent to address this sin / evil / breach of justice. In doing so the parents are fulfilling a role that they have voluntarily adopted, especially these days. Yet our pacifist co-religionists fail to extend a similar legitimation to Christian officers of the state. Is this coherent?

Once the dam is breached, the rest of the case for Christians to enforce the law with force must be admitted; if it is my duty to protect Timothy from Molly as a parent, it is surely equally my duty to protect Timothy from the rampaging criminal. If I can do that as a parent, I can surely do it as a officer of the law. And if I can use force to stop the local criminal, it follows that I can use the police to protect a small island from pirates, or an army to protect a state from invaders. It’s interesting to note that modern pacifists focus on military activities, and usually draw a distinction between that and the police role of maintain law and order in a society. This distinction presumably was accepted in Pennsylvania under Quaker rule; a feature of the persecution suffered by the pacifist Mennonites in Europe was that they were subject to crimes and were not protected by their host state.

Conclusion

Despite its relatively respectable heritage, the idea that pacifism is mandated by the bible does not seem correct. Instead it is best seen as an acceptable idea, but one that we should be careful about imposing on believers; one of those ideas that Paul seeks to defuse debate about in Romans 14. To my mind, the main objection to the idea is the impact on evangelism; it can become a barrier to considering becoming Christians to be told they should forgo state protection, though most modern pacifists do allow seeking police protection. Yet such a test must not be applied too widely, as there is a dangerous temptation to water down the requirements of church involvement; as ever these issues need clear thinking – aka ‘theology’. The modern church is not good at this!